From the Desk of Dr. Accad

Your Blood Pressure Is 125/82. Is This Too High?

This article was originally published on December 1, 2017

As some of you may know, a new definition of hypertension (high blood pressure) was recently proposed by the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and 9 other sponsoring organizations.

According to the new definition, if one’s resting blood pressure (measured properly) is more than 120/80, it should be considered “elevated.” And if one’s BP is more than 130/80, then the person with that blood pressure should receive a diagnosis of hypertension.

Needless to say, the proposed definition has generated a lot of controversy. If all doctors adopted the new definition, that would create millions of new patients overnight, and a third of American adults would be considered to have a chronic disease!

What’s more, anyone with a blood pressure over 120/80 would be advised to have close medical follow-ups: repeat visits every 3-6 months, according to the new guidelines.

If the new definition seems a little extreme to you, you’re not the only one. I also find myself at odds with the document, and other doctors and colleagues are equally skeptical. But how are we to make sense of the new definition? Surely there must be some basis for it?

The answer is yes and no. But before we can judge the recommendation itself, we need to understand better what high blood pressure is and how it can affect us.

Basic facts about the blood pressure

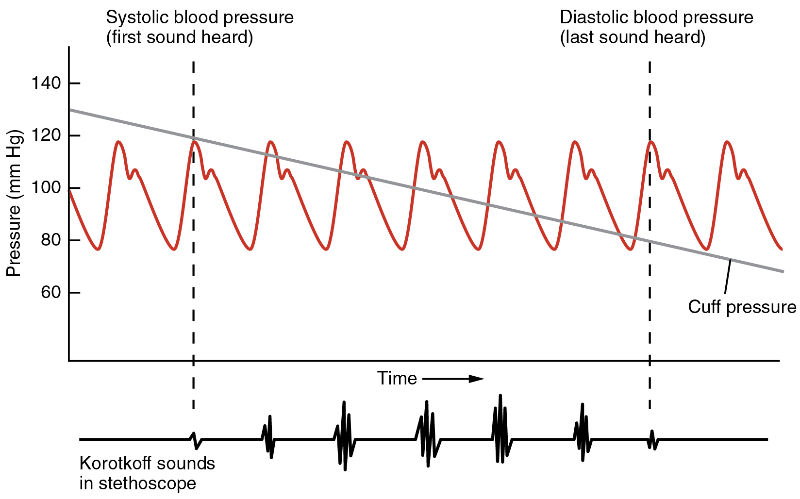

The blood pressure is the force exerted by the blood against the walls of the blood vessels with each heartbeat. As you can imagine, the pressure goes up as the heart squeezes and then falls as the heart relaxes. That’s why the blood pressure is represented by 2 numbers (systolic and diastolic). For example, 118/76 or 150/83.

Image Attribution: OpenStax College via Creative Commons CC BY 3.0

The blood pressure normally changes all the time. Even if you are resting quietly, there will be small pressure changes from beat to beat related to your breathing pattern, your state of alertness, and other factors.

Then, if you start moving, the blood pressure will also change in response to your movements. And the blood pressure changes throughout the day: it is higher when you just wake up (you get a jolt of adrenaline to get you out of your slumber!), it is lower after you eat (blood goes to your gut to help digest), and much lower when you sleep. It is higher when you are more stressed, and lower when you are more relaxed.

As you can see, the blood pressure is not one set of numbers, but a quantity that varies all the time.

Defining “the” blood pressure

Many decades ago, when doctors began to suspect that a high blood pressure could be associated with health complications, they came up with some procedure to standardize the measurement to reduce the inherent variability. One standard procedure is to measure the blood pressure after someone has rested quietly for a few minutes, and to repeat this on 3 occasions and average the 3 numbers.

That’s what is commonly referred to as the blood pressure. But even with this procedure, there are is lot of variability and many pitfalls in measurement that one has to keep in mind.

Lower is better

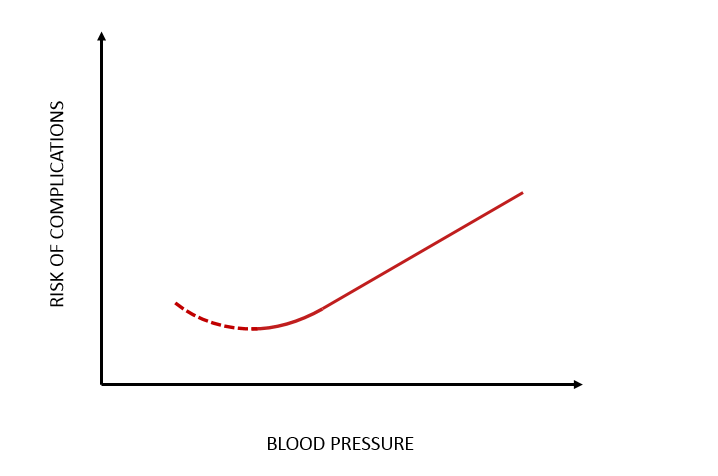

Now, with this standard way of measuring the BP, doctors and scientists established beyond any doubt that a higher resting blood pressure indicates a higher risk of complications in the future. That’s true for either the top (systolic) or bottom (diastolic) number.

For example, if we take a group of people whose systolic BP is between 101-110 today, the number of individuals among that group who will have heart attacks, strokes, or kidney failure in 10 years will be very low and lower than in a group of people whose systolic BP is between 111-120. In turn, the number of people who will experience complications in that group will be lower than for a group of people with systolic BP 131-140, etc.

In a sense, then, “lower is better” so long as people are otherwise feeling well. Of course, the blood pressure shouldn’t get too low or we could faint! Fortunately, the body usually keeps that from happening, but there are nevertheless some instances where we need to be careful about low blood pressure.

For example, there is one caveat with elderly patient who may paradoxically have a higher risk of heart attacks if their diastolic blood pressure is too low. Otherwise, if we are talking about blood pressure in general, I think it is fair to say that lower is better.

At any rate, the relationship between the blood pressure and the risk of health outcomes can be described according to the graph below, and where the dotted “J” shaped indicates that in some instances a low BP may not necessarily be better:

Atherosclerosis plaque. Image attribution: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain, N.I.H.

But…

So, we should have a blood pressure as low as possible, right? And , if so, how low should it be, and what’s considered normal?

Here’s where we can get in trouble.

The lowest point on the curve is not a fixed number that we can identify. The curve gradually increases from the range of normal and there is no identifiable number that says “above this, your risk is too high.” Calling any number “normal” or “abnormal” is tricky.

Because the curve is drawn from large population studies, and the “risk” of complications pertains to groups and not to individuals, is not all that clear that any given BP number imparts the same risk to different people.

For example, for one person a BP of 135 may be too high, but for another it may be just fine. People’s bodies may respond different to a given blood pressure due to genetic predispositions, or because their bodies are healthier in other ways.

So, the numbers picked in the new definition of hypertension (and in the old one, for that matter) are, in a very real way, arbitrary. To say that 120/80 or less is “normal,” and anything above 120/80 is abnormal, is really stretching the meaning of normal and abnormal. The definition attaches to specific numbers a significance they do not have.

Population health versus individual health

The new definition is really a tool for population health, rather than of medical care. The committees that come up with definitions of hypertension are really saying that as a population, it would be best to have an average blood pressure lower than it currently is in the United States.

That may very well be true, but doctors should always be mindful of the individual person they are treating, and not simply thinking about that as statistical data points.

If, on the one hand, we can argue that “lower is better” and that a BP less than 120/80 is more desirable that a BP > 120/80, we should be very mindful of the potential negative consequences of turning that number into a criterion to define normal and abnormal.

Risks of overdiagnosis

There are many potential negative consequences of being too eager to make the diagnosis of hypertension, and these consequences have been well documented in the medical literature over the years:

-

For example, imagine walking into the doctor’s office for a routine check-up and walking out with a “label” of hypertension or elevated blood pressure. There can be negative psychological consequences.

-

We know that some people can start feeling sick, experience headaches or other symptoms just from being told they have high blood pressure. This is the so called nocebo effect and can lead to sick calls from work and decreased productivity.

-

Also, the increased risk of complications from having a mild elevation in the blood pressure must be placed in the context of the patient. Some patients already have many other health problems to deal with. Why add to these problems with a new diagnosis that is unlikely to change the course of things?

-

Importantly these days, a label of hypertension can also have serious financial impact on life insurance and health insurance premiums. And once someone is labeled as having an elevated blood pressure, more doctor visits will be expected, and probably more treatments.

-

Although blood pressure medicines are generally very safe, complications sometimes occur. This is particularly true for elderly patients whose body can have a hard time adjusting to changes in blood pressure and, as result, may be more prone to falls or faints.

The way forward

So, how do we sort all that out?

I personally think that we should move away from making decisions according to arbitrary cut-off numbers. It is important to be mindful of the relationship between the blood pressure and complication described by the graph above, but it is also important to be mindful and observant of all the specific patient considerations that could bear on how we label patients.

We don’t want to label and treat patients unnecessarily, and we also don’t want to ignore and miss opportunity to intervene and avoid complications. In fact, I think that sometimes adhering rigidly to cut-off numbers can causes people to be under-treated.

Medicine is a fine art. A doctor should be ready to not treat 2 patients with the same blood pressure in the same way, but take into considerations all the necessary factors. A few years ago, Dr. Herbert Fred and I published an article outlining what we consider a sensible approach to the question of hypertension. In some cases, cardiovascular testing can be helpful to help differentiate the patient who needs more intensive intervention from the one who does not.

At any rate, the main point that I would like to make is that definitions of “high blood pressure” based on cut-off numbers are artificial and potentially harmful. Doctors should not treat individual patients on the basis of population health considerations, however well intentioned these might be.

Best regards,

– Dr. Accad