From the Desk of Dr. Accad

When Endurance Athletes Have "Hearts of Stone"

This article was originally published on November 4, 2017

I have just returned from attending a course on the “Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in Athletes,” hosted by the University of Washington medical school in Seattle. It was a terrific conference at which academic leaders in the field gave updates on the latest research.

Dr. Aaron Baggish, from the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, summarized two recent studies that have persuasively shown that coronary calcifications are more common in long-term endurance athletes compared to more sedentary controls.

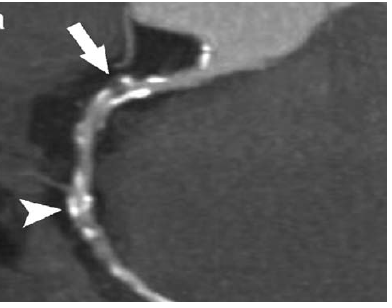

When the studies were published this past summer, Dr. Baggish was asked to write an editorial commentary to share his perspective. That editorial was provocatively subtitled "Hearts of Stone." The phrase refers to the appearance on CT scans of hearts with heavily calcified arteries as shown in this image:

Calcium in coronary artery detected by CT scan. Image attribution: Wikimedia Commons

Background

In the last several years, a few reports were published suggesting that endurance athletes may be more prone to having build-up of plaque and calcium in their coronary arteries. Those reports presented a paradox, because we also know beyond any doubt that regular, moderate level exercise promotes cardiovascular health and longevity. The studies raised the concern that exercise could be harmful after a certain point.

However, those earlier reports included only small numbers of athletes and often had no control group, so they could not demonstrate that it was the exercise itself that played a role in plaque development.

For example, it could be that some middle-aged athletes are healthy as far as exercise is concerned, but not so healthy as far as dietary or smoking habits are concerned. Middle-aged athletes may also come to exercise after a period in their life when they were not so healthy. So, perhaps the increase in coronary plaque seen in the studies had to do with those earlier exposures and had actually nothing to do with exercise.

The new studies

The first of the two new studies compared healthy Masters level athletes (men and women, mainly cyclists and runners) to healthy controls who were physically active but did not engage in endurance sports at a high intensity level. None of the participants were former smokers, and all had very good metabolic profiles (cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar, etc.). The mean age was about 54.

Compared to the control group, the Masters level athletes had higher amounts of coronary calcium, more plaques involving more of the coronary arteries, and more bulky plaques that could potentially interfere with blood flow.

More concerning was the fact that 14% of the male Masters level athletes had detectable scar tissue in the heart muscle, compared to none of the male or female controls. One female athlete also showed some evidence of scar tissue. The scar tissue was not always correlated with the presence of coronary plaque.

The second study involved a group of middle-aged male athletes who engaged in competitive sports or in regular physical activities. The group included all comers, as far as lifestyle and metabolic health is concerned: some of the men were either current or former smokers, some men were being treated for high blood pressure, and some men had high cholesterol.

There was no control group, but the athletes were divided according to “lifelong exercise volume” and intensity of activity. There was clear increase in coronary calcification and plaque with increasing volume and intensity of exercise, and the relationship between exercise and plaque build-up remained, even after making adjustments for baseline risk factors, such as cholesterol or smoking.

My opinion

These are the first studies to raise a credible concern about an effect of “too much exercise” on heart health. The first study is particularly concerning, showing that intense endurance exercise is associated with plaque build-up and scar tissue in the heart, even in patients who have no other objective risk factors for heart disease.

However, we should not jump to conclusions.

First of all, the studies are “cross-sectional,” which means that they have examined subjects at one point in time. Cross-sectional studies are less helpful at establishing cause-effect relationship compared to longitudinal studies.

Also, the studies show that only some, but not all, high-intensity endurance athletes develop concerning heart findings. In fact, as a group, elite level athletes do very well. Long-term cohort studies have shown excellent longevity among Olympic level and Masters level athletes. So, is there a genetic predisposition to the harmful effects of exercise that we are unaware of and that explains why only some athletes demonstrate increased plaque build-up?

More important, we have to remember that we cannot separate the effect of exercise itself from the behaviors that accompany the decision to exercise intensely. Those behaviors cannot always be captured in a scientific study.

Factors that are difficult to capture scientifically have to do with mental stress, mental and physical fatigue, and patterns of rest and recovery. Does high intensity exercise affect the heart equally in those who exhibit better mental and physical balance compared to those athletes who are always pushing the limits of tolerance? We don’t know the answer to those questions.

What to do?

At the Seattle conference last week, Dr. Baggish offered the following excellent advice to middle-aged athletes:

-

Don’t ignore lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet: exercise does not immunize against heart disease

-

Health and performance are 2 different things. Opting for one may not lead to the other

-

Don’t overlook the importance of rest.

-

Warm-ups and cool downs are important. Most deaths during endurance events occur at the beginning and toward the end of races, and even after the race is over.

-

Practice careful event preparation.

-

Respect a virus: don’t race or train intensely if your body is generating an immune or inflammatory response. There might be a connection between inflammation and athletic heart disease.

Dr. Baggish did not address the question of cardiovascular screening. It’s a controversial issue because mass screening has not been shown to necessarily lead to reduced cardiovascular events.

From my standpoint, the decision to screen is very personal and should start with the athlete. If the athlete has no interest in changing his or her way, in the event abnormalities are discovered, there is no point in screening.

On the other hand, screening can reassure: there may not be any evidence of plaque build up, in which case the long term cardiac prognosis is excellent. Screening can also serve as a benchmark for those athletes who think they might modify their routine on the basis of the new information.

Also, even if screening does not change behavior, an athlete who knows he or she has coronary calcifications may be less likely to ignore future warning symptoms and signs.

If you live in the SF Bay Area and would like to explore the topic more with us, give us a call. We do our best to provide timely and reasonable advice.

Best regards,

– Dr. Accad